When sifting through historical records, it’s not uncommon to accept at face value the recorded events, particularly when the source is contemporary. But people remember events differently, either naturally or by design. We observe our world through a lens thickened by expectation and human experience. Even well-documented historical events have gaps.

The escape of King Charles II is a good example of this. The details of his flight following the Battle of Worcester are contained in the collection of contemporary accounts known as the Boscobel Tracts. These were written during the Restoration, over a decade after the escape. But there is one other account, written mere weeks after the incident, that includes a detail not mentioned in the Boscobel Tracts. A curious mind wonders why.

Following the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651, a defeated Charles spent six weeks dodging Cromwell’s men and finally managed to escape to France.

Image unchanged

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

For a highlight of his adventures, see my series, “Finding the Fugitive King”, starting with (Part 1): White Ladies and Boscobel House.

Charles arrived in Paris with Lord Wilmot on October 19, 1651. The Venetian Ambassador in France, Michiel Morosini, wrote a letter[1] to the Doge of Venice on November 7, 1651 giving him the news of the escape. The tone of the letter suggests that the ambassador received this account directly from Charles.

The king of England entered Paris on Wednesday evening, being met by the Duke of Orleans, the queen his mother, the Duke of York and many grandees of the Court as well. His suite consisted of a gentleman and a lackey. His dress was more calculated to move laughter than respect, and his aspect is so changed that those who were nearest believed him to be one of the lower servants. He relates that after the battle, he escaped with a gentleman and a soldier, who had spent most of his days in highway robbery and had a great experience of hidden paths. Thus accompanied the king travelled by night, always on foot, as far as the remote parts of Scotland, but finding no means for embarking or place of safety, he had himself shaven, as a more complete disguise, and decided to return to England. There by ill fortune he was recognised by a miller, who began to shout to raise the country. Though destitute of the royal trappings, he did not lack prudence and courage to extricate himself from such a perilous adventure, as he hurried into a neighbouring wood, where he hid among the branches of a tree. In spite of the number and energy of the countrymen they never thought of raising their eyes, although the wood was full of men looking for him. When night came he took the way to London, where he arrived without being recognised and remained there in the same disguise. He was lodged in the house of a woman who got a ship for him, and to avoid risks in going through the city, he wore her clothes, and with a bag of washing on his head he got to his ship in safety and so crossed.

There are many points of agreement with the Boscobel tracts: the altercation with the miller, Charles hiding in a tree while soldiers searched the woods. Even the way that Morosini describes Charles, as wearing rough clothing and “his aspect is so changed that those who were nearest believed him to be one of the lower servants,” match the later accounts.

But the most curious section involves the statement, “He relates that after the battle, he escaped with a gentleman and a soldier, who had spent most of his days in highway robbery and had a great experience of hidden paths.”

Fact or fiction?

If truth, then why was this detail not included in the Boscobel tracts, and if fiction, what was the purpose of its creation?

The most compelling reason to shrug this off as an embellished story, given to an easily impressed ambassador, was that it simply wasn’t included in any of the Boscobel narratives. However, around the time that Charles arrived in Paris, rumours were circulating around London that a highwayman was a party to his escape.

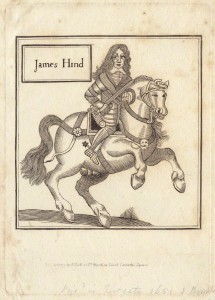

Two days after Morosini’s letter, an infamous Royalist highwayman, Captain James Hind was captured and questioned for any part he might have played in Charles’s escape.

Though Hind confessed to the various crimes of highway robbery, manslaughter, carrying the King’s goods to Ireland, and the most damning of all, fighting at Worcester with the King, he denied this one accusation. (For a detailed account of Captain Hind, read my article A Royalist Highwayman.

Perhaps this had been Charles’s attempt to protect those who had helped him by clever misdirection, for what would be more sensational and fuel people’s imagination more than an outlaw assisting a king? Certainly the most outrageous portion of Morosini’s letter, that Charles went to London and disguised himself as a washerwoman to sneak aboard a ship, may have been to direct attention away from Shoreham, from where he did sail. It would not have been difficult for Parliament to discover which captain had ferried him across the channel had they known the true port of departure.

But could Charles not have equally protected the Penderells, the Lanes, the Whitgreaves, the Wyndhams and everyone else in between without the tale of a highwayman? Recall that Charles did arrive in Paris with his good friend, Lord Wilmot, who could have been singly credited with the enterprise. In fact years later, Wilmot did become the star of the adventure, thanks to the Boscobel tracts. But at this time, based on Morosini’s subsequent letters, Wilmot was not given a strategic role in the escape.

What really happened?

For the historian, this is another gap to be filled and a puzzle to be solved. But for the fiction writer, therein lies the golden question, ‘what if?’

[1] British History Online: ‘Venice: November 1651’, in Calendar of State Papers Relating To English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 28, 1647-1652, ed. Allen B Hinds (London, 1927), pp. 202-206 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/venice/vol28/pp202-206 [accessed 19 December 2014].

‘What if’ is the jam over the bread and butter of any researcher with an eye to serious fiction.

I think Charles made up the highwayman story to protect the honest people who helped him, but also because of his sense of humour. Quite simply he was having the ambassador on. All his life he liked to poke fun at those who took themselves too seriously, and there were plenty of those at the French court. It was also quite true that this adventure forever altered him. Having stared at the underbelly of the beast who had deposed his father, and shared honest interaction with earnest and loyal common folk, he had learned a new perspective on the civil war and the English people, as well as life itself, the darkness and the glory of human nature. A lesson that would never leave him.

As for the highwayman, he could have existed. And that is very sweet jam indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Charles did not suffer fools gladly and certainly enjoyed a good jest. Sweet jam for sure!

LikeLike

What brilliant fodder you have at your fingertips. Keep us posted about the book!

LikeLike

Thanks, Linda. Definitely will.

LikeLike

[…] ← Puzzles in the Historical Record: The Highwayman Did It? […]

LikeLike

Wow, marvelous blog layout! How long have you been blogging for?

you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your

website is great, let alone the content!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I absolutely love your blog.. Great colors & theme.

Did you make this website yourself? Please reply back as

I’m hoping to create my own personal website and want to

know where you got this from or just what the theme is named.

Thank you!

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. The layout is one of the templates available through WordPress. Very easy to use.

LikeLike

[…] For another story that I stumbled on while procrastinating researching in British History Online, check out Puzzles in the Historical Record: The Highwayman Did it? […]

LikeLike