I am especially pleased to be able to turn over the blog today to acclaimed author, Deborah Swift. Deborah is best known for her historical fiction novels which are set during the Restoration. Her stories are rich in historical detail and are a direct portal to the 17th century.

Deborah’s latest series revolves around some of the women mentioned in Samuel Pepys’s diary. The first in the series, Pleasing Mr Pepys, was one of my favourite reads this year. I couldn’t put it down. The second book in the series, A Plague on Mr Pepys, has just been released July 5th and is as great a read as is the first!

In addition to writing page-turning historical fiction, Deborah writes excellent articles about everyday life in the Stuart Era. In this guest post, she discusses the Great Plague and the treatments concocted to ward off the pestilence.

Welcome Deborah!

Quackery and 17th Century Medicine by Deborah Swift

Whilst researching The Great Plague for my latest novel, I became fascinated with the idea of ‘Quackery’ – the fake remedies sold to unsuspecting purchasers as ‘cures’ or ‘preventions, by unscrupulous con-men.

Whilst researching The Great Plague for my latest novel, I became fascinated with the idea of ‘Quackery’ – the fake remedies sold to unsuspecting purchasers as ‘cures’ or ‘preventions, by unscrupulous con-men.

The 17thcentury saw some significant scientific discoveries (such as William Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of the blood (1628) and Anton van Leeuwenhoek’s research into what became known as bacteria (1683), but physicians still did not know what caused disease. So when an infection like the Plague became an epidemic, doctors were powerless. Quacks then came sneaking out of the woodwork to prey on people’s fears, and great amounts of money could be made by ‘cures’.

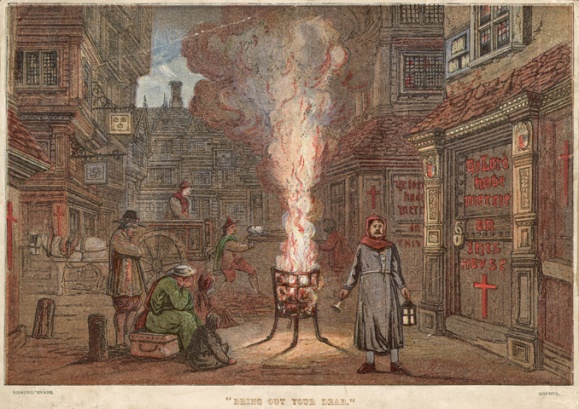

Vapours

The most common cause was to blame vapours or ‘miasmas’, in other words bad smells, which led to the popularity of tobacco and smoking as a remedy, and many common treatments consisted of making the room and the patient smell sweet. This is why doctors wore full body suits – with a leather ‘beak’ that was crammed with flowers and herbs – so that they would only smell the sweetness of the pot-pourri.Those employed in the collection of bodies frequently puffed on pipes to avoid catching the plague. In 1665 the College of Physicians issued a directive that brimstone ‘burnt plentiful’ was a cure for the bad air that caused the plague.

Animal Magic

Many quack cures were based on the use of animals, something we would find totally abhorrent today.

Many quack cures were based on the use of animals, something we would find totally abhorrent today.

For example in 1641, Thomas Sherwood, a London “practitioner in Physick,” wrote a book of cures called The Charitable Pestmaster. This featured, amongst other useless remedies, “the puppy cure.” The cure was especially useful for the old and weak, Sherwood explained:

“Therefore you may lay upon the pit of the stomach of the sick a young live puppy, and if the sick can but sleep the space of three or four hours, they shall recover presently, and the dog shall die of the plague.”

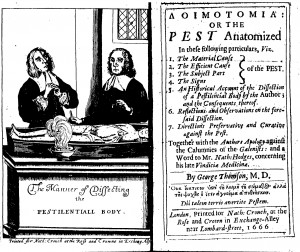

Another physician, George Thomson, performed an examination of a plague victim and, as a result of found himself the victim of the plague. He tried to cure himself using his own chemical remedies—but all his usual remedies failed. Fearing he would die, he resorted to a method that was apparently in common use; the “toad cure.”

Thomson prepared his toad “in as exquisite manner as possible,” and wrapped it in a linen cloth. He then put the toad on his stomach and left it for a few hours. Weirdly, the dried toad swelled up “to the bigness that it was an object of wonder.” According to Thomson, the dried toad “doth draw the pestilential poison so into its body.” Other animals used included chickens and pigeons. It must have been an odd sight to see patients strapped into bed with such a menagerie. It is also interesting to realize that the more extreme remedies were actually not considered quack remedies at all, at the time.

Potions

Common potions were Theriac– a mixture of treacle and various herbs. Sounds innocuous, doesn’t it, until you realize it also contains viper flesh and opium. The brew was left to ferment for several years to thicken and increase its potency. It was applied as a salve or, unlikely as this sounds, it would be eaten.Other popular ingredients includedmercury and arsenic. It seemed to follow the principle of “the hair of the dog,” in which a concoction containing poison from a serpent would counteract other poisons.

I can’t help feeling that the cures were probably also responsible for quite a few deaths. Many potions were sold by pedlars door to door, a process known as ‘making gold from goose-grease’, because many ‘cures’ contained no active ingredients at all, just lard, or water and dye.

Quack’s End

Large cities such as London attracted quacks up until the 19thCentury because England had weak regulations against their practices, whereas other European countries had harsh regulations to protect the public and maintain the ‘professional’ status of trained physicians. In 1748 an attempt was made to stop the sale of medicines by anyone except doctors, but by then many were fond of their cunning-women, astrologers and quacks, just as we are fond of our reiki healers, acupuncturists, herbalists and dieticians today, and there is a large debate about the efficacy of certain medicines or cures even today. It was only in 1858 that a ‘Medical Register’ of qualified doctors was set up, and effective medicine is an ever-moving target.

My Favourite Quack Plague Cure

This has to be Bradley the Botanist’s coffee cure of 1721. Unfortunately it was too late for my characters in ‘A Plague on Mr Pepys.’ In his treatise;The virtue and use of coffee, with regard to the plague, and other infectious distempers’’ Bradley wrote that coffee “is of excellent Use in the time of Pestilence, and contributes greatly to prevent the spreading of Infection.”

He was obviously quite a public-spirited individual;“At this time, when every Nation in Europe is under the melancholy Apprehension of an approaching Plague or Pestilence, I think it the Business of every Man to contribute, to the utmost of his Capacity, such Observations, as may tend to the Service of the Publick.”

Bradley explained that in Turkey where the Plague is almost constant, it is ‘’seldom mortal in those Families, who are rich enough to enjoy the free Use of Coffee.” So there you have it. Should the plague approach, your nearest Starbuck’s is as good an answer as any.

Bibliography:

The Elizabethan Underworld – Gamini Salvado

The Great Plague – Moote and Moote

Maldies and Medicine – Evans and Read

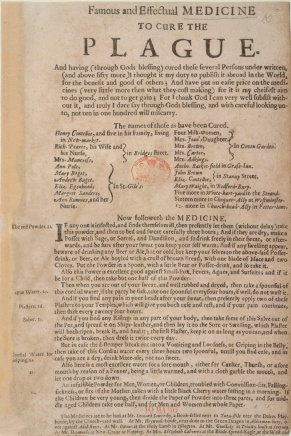

British Library: Advertisement for Medicine to Cure the Plague

BBC History: Samuel Pepys: Teacher’s Resources

About A Plague on Mr Pepys

A Plague on Mr Pepys, the second book based around the women in Pepys’s famous Diary is out now.

‘a great story that explores the workings of the hearts of the characters, touching on themes like family, social crisis at the time of the plague, and the morbid desire to gain wealth at any cost … A Plague on Mr Pepys is a historical novel that scores on multiple levels’ Readers Favorite 5*

‘Laced with emotional intensity and drama’ Readers’ Favorite on Pleasing Mr Pepys

A Plague on Mr Pepys is available in eBook and paperback through Amazon. Connect with Deborah onTwitter (@swiftstory), Facebook, and her Website.

It makes me wonder what sciences we adhere to today will look like to doctors in the future:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Kwakzalverij in de 17e eeuw. […]

LikeLike

[…] Quackery and 17th Century Medicine […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love thiis

LikeLiked by 1 person