The English Civil War (1642-1651) marked a revolutionary period in England. On the great political stage, Parliament waged war against the Crown, culminating in the execution of the king and the creation of England’s first and only republican state. The upheaval of war sparked a revolution of a different kind. People re-evaluated their religious beliefs and role in society, leading to the revolutionary democratic ideals of the Levellers. Women found themselves in the forefront during years of conflict, finding agency in the political struggles.

The Levellers were a political movement that rose to prominence between 1645 and 1649. They were initially on the Parliamentarian side during the English Civil War but became Parliament’s harshest critics over the settlement of the country, following the king’s defeat and subsequent execution. Using the power of the printed word, the Levellers lobbied for freedom of religion, freedom of speech, suffrage for all Englishmen, elimination of excises for the poor, and justice under the law. The Levellers’ values were summarized in Thomas Rainsborough’s iconic speech at the Putney Debates, when the terms of a new constitution were being argued:

“I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest he.”

But what about the “she” in England—where was her voice?

While the Levellers did not espouse women’s suffrage, formidable Leveller women like Elizabeth Lilburne and Katherine Chidley made their mark in history and arguably formed the backbone of the movement.

Elizabeth Lilburne

The history of the Levellers usually starts and ends with the man who was its heart and soul, John Lilburne, also known as Freeborn John. But he would not have survived without the help of his wife, Elizabeth Lilburne, who saved him on a couple of occasions.

Elizabeth Lilburne (née Dewell) had been the daughter of a London merchant, and while her date of birth has been recorded as 1641, this was the year of her marriage, not the year she became a person. Theirs was a love match and a perfect pairing of ideals. Her radical beliefs preceded her time with John, having been a member of a Baptist congregation in London. During the Leveller years, she had often been affectionately called Queen Bess by the pamphleteers.

Except for brief periods of peaceful domesticity, their home life was tumultuous owing to the many times that John had been imprisoned for his political writings, first against the Church and Crown, and then later against Cromwell and Parliament.

Elizabeth met John in 1638 after his imprisonment for printing and distributing pamphlets promoting religious toleration for all non-conforming congregations. The Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London, on behalf of the king, had heavily regulated and controlled the press. As punishment, John had been whipped and pilloried before being thrown into prison. His plight had sparked a series of demonstrations around London. Elizabeth was so moved by his situation that she went to visit him, and a relationship developed during his two-year incarceration.

They wed in September 1641 and enjoyed an idyllic first year, until war broke out in October 1642, prompting John to join the army. A month later, Royalist forces captured John and his men at Brentford and imprisoned them at Oxford. Instead of treating them as prisoners of war, the Royalists planned to execute them for high treason. Elizabeth had learned of their intention and relentlessly petitioned Parliament for assistance. Her perseverance paid off, and Parliament issued a declaration that any executions the Royalists held would be reciprocated in kind.

Days before the sentence was to be carried out, Elizabeth, who was in her last months of pregnancy, rode to Oxford along treacherous winter roads and endured hardships to deliver Parliament’s response. A true heroine, not only did she arrive in time to save her husband’s life, but she saved the lives of the other prisoners. Had John Lilburne been executed then, it’s very likely the fledgling Leveller movement would have perished as well.

A few years later, after the king had been imprisoned and Parliament had assumed control of the country, the ideals for a new constitution and equitable settlement for the country were on the hot seat. The Levellers were at the forefront of those debates, but as Parliament secured their power, key Leveller demands were laid aside. John Lilburne now turned his pen against Parliament and was in and out of prison over the publication of incendiary pamphlets. Elizabeth smuggled out his writings and had them printed through other Leveller presses. When she was banned from visiting with him, she protested to Parliament for her husband’s mistreatment, as prisoners were dependent on family for their needs.

When John Lilburne and the Levellers heightened their criticism of the government and turned their focus to Oliver Cromwell in the publication England’s New Chains Discovered, John and three others found themselves imprisoned for treason. Elizabeth Lilburne, together with other Leveller women, Katherine Chidley, and Mary Overton, organized the unprecedented All Women’s Petition and obtained ten thousand signatures.

On April 25, 1649, Elizabeth and a host of women marched into the House of Commons to deliver their petition. The MPs dismissed their demonstration, sneering that it was strange that the women dared to petition Parliament, to which one protestor tartly replied, “It was strange that you cut off the King’s head, yet I suppose you will justify it.” When told to go home and wash their dishes, one protestor retorted, “Sir, we have scarce any dishes left us to wash, and those we have not sure to keep.”

In response to Parliament’s refusal to hear them, Elizabeth published and distributed her own pamphlet. In her words:

“That since we are assured of our creation in the image of God, and of an interest in Christ equal unto men, as also of a proportional share in the freedoms of this commonwealth, we cannot but wonder and grieve that we should appear so despicable in your eyes as to be thought unworthy to petition or represent our grievances to this honourable House.”

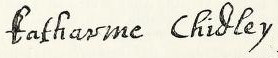

Katherine Chidley

Katherine Chidley was another woman who was at the heart of the Leveller movement. Even a decade before the civil war and well before the Leveller movement spread, Katherine was a fearsome woman with a pen.

Katherine and her husband, Daniel Chidley, were haberdashers who moved their family to London in 1629 and founded a non-conformist ministry in Stepney. She was a radical evangelical who preached that people should have the right to minister to themselves instead of following the ecclesiastical Church of England. Not only was she a fierce proponent of religious reform, she advocated religious equality for women. In one of her publications, she wrote:

“I pray you tell me what authority this unbeleeving husband hath over the conscience of his beleeving wife. It is true he hath authority over her in bodily and civil respects, but not to be Lord over her conscience.”

Her views drew the scorn of Thomas Edwards, a prominent Presbyterian minister who believed that the independent puritan sects would cause the destruction of society and corrupt family values. Edwards dismissed Katherine as an “audacious old Jael”, but his insult backfired. In her response, Katherine employed the tradition of strong biblical women, like Jael, who served a higher authority and who were called upon to judge kings. Edwards must have felt sufficiently threatened by her words, for while he claimed it would be beneath him to debate a woman, debate her he did. In the end, he was no match for Katherine’s wit and came up short in every argument.

During the All Women’s protest, Katherine was not only a leading organizer with Elizabeth Lilburne, she is considered to have written The Humble Petition of Divers Wel-Affected Women which garnered the ten-thousand signatures. To have obtained so many signatures from the women of London, Westminster, Southwark, and other surrounding hamlets, implies a widespread and organized community of revolutionary women.

The petition’s core message was that Parliament engaged in the same tyranny that they had fought against the king. And when Parliament delayed releasing the men, Katherine stood at the pulpit of her ministry and preached for their release.

Elizabeth Lilburne and Katherine Chidley were revolutionary women at the forefront of a unprecedented democratic movement when women were considered subordinate to their fathers and husbands. The Leveller ideals spread and gained momentum through effective pamphleteering, and both these women directly contributed to the words that awakened a nation.

Further reading:

- The Leveller Revolution, by John Rees

- The Weaker Vessel, by Antonia Fraser

- “Commoners Wives who Stand for their Freedom and Liberty: Leveller Women and the Hermeneutics of Collectivities”, by Melissa Mowry.

- “A Hammer in Her Hand: The Separation of Church from State and the Early Feminist Writings of Katherine Chidley”, by Katharine Gillespie.

This article was originally published in Historical Times, July 2023 Civil War edition.