On my last blog post, I featured an exciting new speculative historical fiction anthology, 1066 Turned Upside Down. I had the opportunity to chat with many of the authors about what inspired them to create this anthology. If you missed Part 1, click here to read.

Today for Part 2, we continue the conversation about their writing and the anthology.

Without further ado, I present Annie Whitehead, Alison Morton, Richard Dee, Carol McGrath, Anna Belfrage, and Joanna Courtney.

Helen Hollick, in Part I of this blog, Annie Whitehead speculated about post-Hastings Britain if Harold had been victorious. What are your thoughts about how England would be different today had the Saxons won Hastings?

Helen: It is usually speculated that had Harold II taken the victory England would, today be more like any of the modern Scandinavian countries. I am not so sure. Would this, perhaps, depend on how ambitious – or cautious, Harold had been? Duke William had sons. Had he been killed at Hastings (which would have happened had he lost, Harold could not have afforded to let him live), would Harold have had to ensure these sons did not pose a future threat? Given the victory could Harold have turned the tables and used the Norman fleet, anchored at Hastings, to sail to Normandy to make the Duchy is own? He had defeated Duke William, and that would mean most of the Norman nobility who had come with William would also be dead. Harold could not have risked Duchess Mathilda rallying troops to her eldest son’s side to avenge her husband. Harold would have had to make certain that William’s sons did not live to fight another day.

So I think we would have had the Norman Conquest in reverse – the English Conquest – and something very similar to the Plantagenet line of succession which followed 1066, only as the Godwinson Line and England being the hub, not Normandy. Harold would have ensured support from the Pope, would have built churches and initiated some form of coherent administration – he might have even built stone castles and introduced a feudal system. He might have gone on to take vast areas of France for his own, either by force or alliance – he had sons and daughters to marry off. Maybe, just maybe, in later years a certain young woman called Eleanor from Aquitaine would have married one of his grandsons and become Queen of England with Harold Haroldson, not Henry II…

You see the possibility for ‘what if’s’ are infinite!

Anna Belfrage, in the anthology, you feature a different perspective than either the Saxons or the Normans and instead write about the King of Denmark, Sven Estridsen. What impact did 1066 have on Denmark?

Anna: Since the beginning of the 11th century, there had been close ties between England and Denmark. King Canute was Danish, his son Hardicanute was half Danish, and some of the more powerful men in Anglo-Saxon England had close personal ties to Denmark. One such man was Harold Godwinson, whose mother was Danish and sister to King Canute’s brother-in-law, Ulf Jarl (or Jarl Ulf, as English speakers would call him). This Ulf was powerful in his own right, and by his wife, Estrid, he had a number of children, one of whom was Sven Estridson, king of Denmark by the time 1066 came around.

Sven Estridson used a matronymic rather than a patronymic name for the simple reason that his claim to the Danish crown came through his mother, a daughter to Sven Forkbeard. He was quite some years Harold’s senior, and I believe he would have been more than happy to see his cousin crowned king of England – this would only strengthen the relationships between the two countries.

Anglo-Saxon England contributed a lot to the building of the Danish state: Anglo-Saxon priests served in the churches, Anglo-Saxon craftsmen built churches and houses, Anglo-Saxon minters helped develop coinage. In Lund, a city presently in Sweden but back then very Danish, archaeological digs have revealed a number of finds engraved with Anglo-Saxon names, indicating there was sizeable colony – both before but definitely after the Conquest. Danish ships traversed the North Sea, laden with pelts and timber going one way, with luxuries going the other.

So of course Sven Estridson watched the development in England with concern – and even more so when Harald Hardrada decided to put forward his own claim. Ever since Harald had come back from his lengthy service at the Byzantine court, he and Sven had been at loggerheads, with Harald (and his brother) insisting Denmark was part of Norway, Sven just as vehemently arguing that if anything Norway belonged to Denmark.

Harald went to England and died at the battle of Stamford Bridge. Sven probably did high-fives, thrilled to bits at being rid of this constant burr up his backside. And then came the news that Harold had died at Hastings, and any joy Sven felt was replaced by trepidation. While William the Conqueror had Nordic blood, it wasn’t exactly as if Sven and William were kissing cousins, and Sven was concerned for all those Anglo-Danes who might lose everything in the coming upheaval. This is why, in 1069, Sven joined forces with Edgar the Atheling and arrived in northern England at the head of a considerable army. York fell to the Northerners (almost happily, I suspect) and William must have passed a sweaty night or two – until he came up with the perfect solution: he would pay Sven to go back home. After all, it had worked before with the Danes.

I am sad to say Sven took the bribe. Off he went back home, leaving Edgar to flee to Scotland and the men of northern England to suffer the vengeance wreaked on them by William, the so called Harrowing of the North. Obviously, at some point Sven was afflicted by second thoughts, and he made a reappearance in England in 1074 or so. By then, his would-be allies were all dead, crushed under the heel of the might Norman boot.

Alison Morton, you take speculative fiction to new levels by introducing your own alternative historical Roma Nova characters into this epic timeframe (1066). What makes alternative history so appealing?

Alison: Just at a moment in the space-time continuum, an event occurs, the timeline diverges and history rushes off in an alternative direction. Nothing is ever the same again. We catch our breath and then, intrigued and fascinated, we explore. Suppose Harold had won at Hastings? What possible future is there for him standing exhausted on the battlefield, and for his country: continuation, then inevitable decline of Saxon culture; economic colonisation by Normandy and France; invasion from Scandinavia; excommunication of the whole of England and an early Reformation? The ‘what if’ list is endless, and that’s not counting the maverick accidents of history.

For a fiction writer, the alternate history framework is a dream. You can let your imagination fly. But there are pitfalls. The world you build must follow historical logic and be both plausible and consistent in order to engage the reader and gain their trust. And you have to have it all worked out before you tap the first key.

And who is to say that in a timeline in many ways similar to ours, but not quite, a remnant of the Roman Empire hasn’t survived? One where women are prominent in the power circles. And one that although small is robust, flexible, wealthy and knows the world’s secrets… Wary yet respectful, others listen to what the Roma Novans have to say.

Alternate history gives us a rich environment in which to develop our storytelling, to explore dangerous themes, even frightening ones, but always fascinating ones. And the writer is, of course, the mistress of her universe.

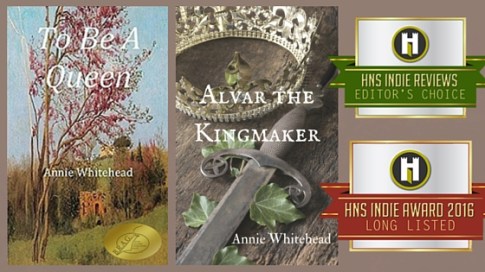

Annie Whitehead, in your novels, To Be A Queen and Alvar the Kingmaker, you focus on the Mercians. What is the source of this deep connection to Mercia?

Richard Dee, you truly go speculative in If You Changed One Thing. You are a science fiction writer mingling with historical fiction authors. How did you get involved in this project?

Richard: For that I must thank Helen Hollick; she has encouraged me ever since I sent her the manuscript of my novel Ribbonworld for her comments.

When she asked me if I wanted to get involved in this project, I thought at first that the two genres don’t really mix. But when you sit down and consider it, writing about the past and writing about the future have one thing in common, they are both connected by the present. Obviously we know nothing of the future but, in some cases we know very little of the past either. So with a little imagination you can weave a tale that takes a fact or an idea and turns it upside down, to coin a phrase.

When most people think of the Battle of Hastings, they naturally think about battles and armies. But in this speculative anthology, many of the stories focus on the women (wives, mothers, and daughters). What are your thoughts on their influence at that time?

Carol McGrath: I am not sure they did have great influence, generally speaking. Legally Anglo-Saxon women could make wills and their property was theirs to distribute as they wished. In reality, this was more often controlled by brothers, uncles and so on. You could not force a woman to marry against her wishes, yet all the time, throughout history, marriages were arranged and girls were pressured into accepting these.

I would say that some women wielded ‘soft power’. Some women could indeed influence husbands physiologically and they sometimes did. Eleanor of Aquitaine famously supported her sons against her husband. None the less, she paid a price for that and was incarcerated for many years by Henry II. Matilda acquired much support against Stephen but it was her son who was eventually crowned a king. She was not. Women did sign charters as witnesses. Queen Emma in the first half of the 11th C was a strong woman by all accounts but at the end of the day King Edward, her son, stripped her of her wealth.

The Godwin women were educated. They learned languages and read and were able to write. Queen Edith had a school for noble women at Wilton Abbey. These women were superb embroiderers. Queen Edith, wed to Edward the Confessor, is also an example of an educated clever woman who was pragmatic after the Norman Conquest and who was permitted to keep her lands. Of course, if she was on side, that looked very good for King William who was marrying off Anglo-Saxon heiresses to his knights post Hastings, commoditizing these women. Edith Godwin was widely respected by scholars, too, at home and abroad. However in 1052 when her family fell out with King Edward she was powerless and banished by Edward to Wilton. She did return to court once the quarrel was mended and the Godwins were recalled. Gytha, Harold’s mother, was physically struck by her son, King Harold, according to a Chronicle when he marched south after Stamford Bridge and she suggested he send his brothers on to meet William at Senlac. He may have taken a wound and this determination to march on suggests his lands and possibly family were under attack. ( The Burning House). However, this resourceful woman, survived Hastings and later was besieged by King William in Exeter for refusing to pay tax. Still, she was let down by the towns people and the Bishop when it looked like the siege would be unsuccessful. So influence, not really, resourceful and memorable absolutely. After all, Countess Gytha did leave England’s shores to go into exile with a great Anglo-Saxon treasure and with a company of noble ladies which probably included Thea-Gytha, Harold and Edith Swan-Neck’s elder daughter.

Joanna Courtney, how did you get into writing?

Joanna: I’ve always wanted to be a writer and I wrote endless stories, plays and Enid-Blyton-style novels as a child. As I became older I wrote short stories in the sparse hours available between raising two children and two stepchildren with over two-hundred stories and serials published in women’s magazines before, finally, I signed to PanMacmillan for my three-book series The Queens of the Conquest, about the amazing wives of the men fighting to be king of England in 1066. I am passionate about history and delving beneath the facts enough to turn them into believable fiction – but it was such a pleasure to step outside the box and have fun with like-minded authors to make a few ‘what if’ scenarios up!

Find out more about the authors:

Anna Belfrage is the successful author of eight published books, all of them part of The Graham Saga. Set in 17th century Scotland, Virginia and Maryland, this is the story of Matthew Graham and his wife, Alex Lind – two people who should never have met, not when she was born three centuries after him.

Presently, Anna is hard at work with The King’s Greatest Enemy, a series set in the 1320s featuring Adam de Guirande, his wife Kit, and their adventures and misfortunes in connection with Roger Mortimer’s rise to power. The first two books of the series, In the Shadow of the Storm and Days of Sun and GloryDays of Sun and Glory are now available.

For more information about Anna and her books, please visit her website. If not on her website, Anna can mostly be found on her blog.

Joanna Courtney cut her publication teeth on short stories and serials for the women’s magazines before signing to PanMacmillan in 2014 for her three-book series The Queens of the Conquest about the wives of the men fighting to be King of England in 1066.

Her fascination with historical writing is in finding the similarities between us and them – the core humanness of people throughout the ages – and her aim with this series is to provide a lively female take on an amazing year in England’s history. She lives in Derbyshire, England.

Connect with Joanna on Twitter (@joannacourteny1) and visit her Website.

Helen Hollick lives on a thirteen-acre farm in Devon. Born in London, Helen wrote pony stories as a teenager, moved to science-fiction and fantasy, and then discovered historical fiction. Published for over twenty years with her Arthurian Trilogy, and the 1066 era she became a ‘USA Today’ bestseller with her novel about Queen Emma TheForever Queen UK ttitle A Hollow Crown.) She also writes the Sea Witch Voyages, pirate-based nautical adventures with a touch of fantasy.

Helen Hollick lives on a thirteen-acre farm in Devon. Born in London, Helen wrote pony stories as a teenager, moved to science-fiction and fantasy, and then discovered historical fiction. Published for over twenty years with her Arthurian Trilogy, and the 1066 era she became a ‘USA Today’ bestseller with her novel about Queen Emma TheForever Queen UK ttitle A Hollow Crown.) She also writes the Sea Witch Voyages, pirate-based nautical adventures with a touch of fantasy.As a supporter of Indie Authors she is Managing Editor for the Historical Novel Society Indie Reviews, and inaugurated the HNS Indie Award. Connect with Helen through her Website, Blog, Facebook, Twitter (@HelenHollick), and through her Amazon Author’s Page.

Alison Morton is the author of the acclaimed Roma Nova alternative history thrillers INCEPTIO, PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO and AURELIA (currently shortlisted for the 2016 Historical Novel Society Indie Award). Her fifth book, INSURRECTIO, (HNS Editor’s Choice) was published in April (http://alison-morton.com/books-2/insurrectio/)

Connect with Alison on her Roma Nova site, Facebook author page, Twitter (@alison-morton), and Goodreads.

Annie Whitehead is a history graduate and prize-winning author. Her novel, To Be A Queen, is the story of Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred the Great, who came to be known as the Lady of the Mercians. It was long-listed for the Historical Novel Society’s Indie Book of the Year 2016 and has been awarded an indieBRAG medallion. Her new release, Alvar the Kingmaker, which tells the story of Aelfhere of Mercia, a nobleman in the time of King Edgar, is available now. Connect with Annie through her Website, Blog, and Amazon Author’s Page.

Thanks so much Cryssa – this has been fantastic

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you and the other authors to give us something creative to contemplate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] conversation will continue tomorrow. Stay tuned for Part 2. 1066 Turned Upside Down is now available in eBook through Amazon and the 1066 Turned Upside […]

LikeLike